Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion.

For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% incrise in hourly earings for every extra year of schooling. For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions.

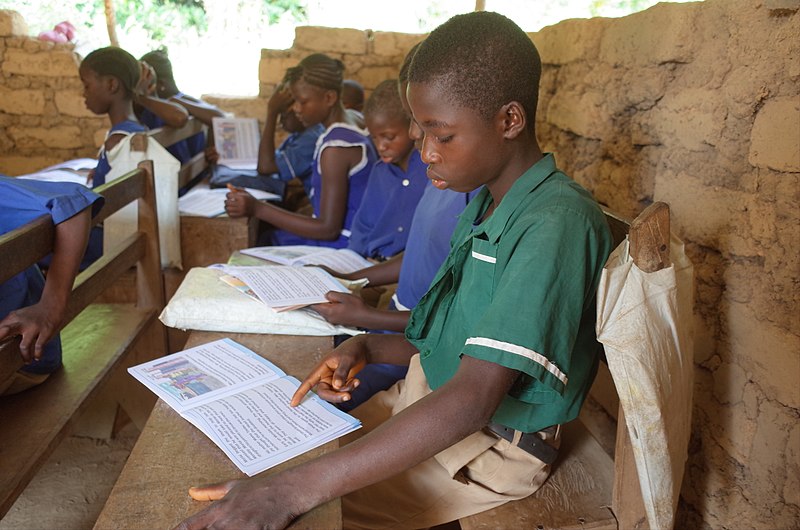

Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school.

Situation of children’s right to education worldwide

Today, education remains an inaccessible right for millions of children around the world. More than 72 million children of primary education age are not in school and 759 million adults are illiterate and do not have the awareness necessary to improve both their living conditions and those of their children.

Another global concern in education is universal access. This term refers to people’s equal ability to participate in an education system. On a world level, access might be more difficult for certain groups based on class or gender (as was the case in the United States earlier in the nation’s history, a dynamic we still struggle to overcome). The modern idea of universal access arose in the United States as a concern for people with disabilities. In the United States, one way in which universal education is supported is through federal and state governments covering the cost of free public education. Of course, the way this plays out in terms of school budgets and taxes makes this an often-contested topic on the national, state, and community levels.

Most affected regions.

As a result of poverty and marginalization, more than 72 million children around the world remain unschooled.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the most affected area with over 32 million children of primary school age remaining uneducated. Central and Eastern Asia, as well as the Pacific, are also severely affected by this problem with more than 27 million uneducated children.

Additionally, these regions must also solve continuing problems of educational poverty (a child in education for less than 4 years) and extreme educational poverty (a child in education for less than 2 years).

Essentially this concerns Sub-Saharan Africa where more than half of children receive an education for less than 4 years. In certain countries, such as Somalia and Burkina Faso, more than 50% of children receive an education for a period less than 2 years.

The lack of schooling and poor education have negative effects on the population and country. The children leave school without having acquired the basics, which greatly impedes the social and economic development of these countries.

Inequality between girls and boys: the education of girls in jeopardy

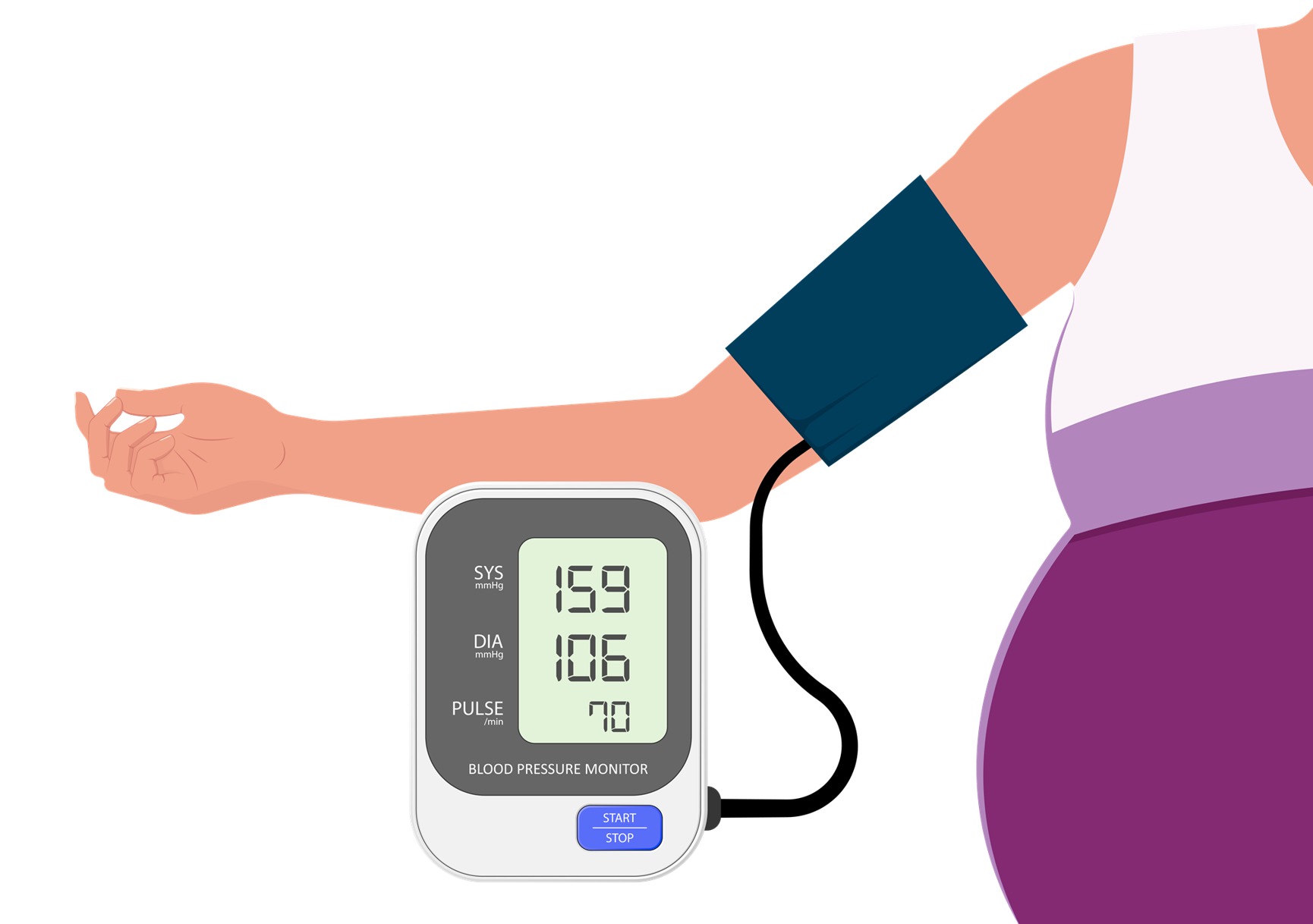

Today, it is girls who have the least access to education. They make up more than 54% of the non-schooled population in the world.

This problem occurs most frequently in the Arab States, in central Asia and in Southern and Western Asia and is principally explained by the cultural and traditional privileged treatment given to males. Girls are destined to work in the family home, whereas boys are entitled to receive an education.

In sub-Saharan Africa, over 12 million girls are at risk of never receiving an education. In Yemen, it is more than 80% of girls who will never have the opportunity to go to school. Even more alarming, certain countries such as Afghanistan or Somalia make no effort to reduce the gap between girls and boys with regard to education.

Although many developing countries may congratulate themselves on dramatically reducing inequality between girls and boys in education, a lot of effort is still needed in order to achieve a universal primary education.

What is unique about the education system from one country to another?

Education is a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. Every nation in the world is equipped with some form of education system, though those systems vary greatly. The major factors that affect education systems are the resources and money that are utilized to support those systems in different nations, as well as how education is organized and administered to students. As you might expect, a country’s wealth has much to do with the amount of money spent on education. Countries that do not have such basic amenities as running water are unable to support robust education systems or, in many cases, any formal schooling at all. The consequences of this worldwide educational inequality are of social concern for many countries, including the United States.

International differences in education systems are not solely a financial issue. The value placed on education, the amount of time devoted to it, and the distribution of education within a country also play a role in those differences. For example, students in South Korea spend 220 days a year in school, compared to the 180 days a year of their United States counterparts (Pellissier 2010). As of 2006, the United States ranked fifth among twenty-seven countries for college participation, but ranked sixteenth in the number of students who receive college degrees (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education 2006). These statistics may be related to how much time is spent on education in the United States.

Results from the most recent Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2015, which is a test administered to 15-year-old students in participating economies every three years, showed that students in the United States lag far behind other high-income countries across different subjects, despite making the most progress in equity compared to other participating countries. The same program showed that by 2018, U.S. student achievement had remained on the same level for mathematics and science, but had shown improvements in reading. In 2018, about 4,000 students from about 200 high schools in the United States took the PISA test (OECD 2019). Countries in the Asian and Nordic regions tend to outperform other countries across all subjects tested (science, mathematics, and literacy), although their educational systems are vastly different in their goals and their administrative systems, suggesting that there is not a single recipe for “success” as measured by PISA.

Analysts determined that the nations and city-states at the top of the rankings had several things in common. For one, they had well-established standards for education with clear goals for all students. Although these countries have well-delineated standards, they do not necessarily outline similar goals. For example, one country may emphasize cooperation, another student growth, or yet another may focus on equality, as in Finland. Another thing the high-performing nations had in common was a tendency to recruit teachers from the top 5 to 10 percent of university graduates each year, which is not the case for most countries (National Public Radio 2010).

Finally, there is the issue of social factors. One analyst from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the organization that created the test, attributed 20 percent of performance differences and the United States’ low rankings to differences in social background. Researchers noted that educational resources, including money and quality teachers, are not distributed equitably in the United States. In the top-ranking countries, limited access to resources did not necessarily predict low performance. Analysts also noted what they described as “resilient students,” or those students who achieve at a higher level than one might expect given their social background. In Shanghai and Singapore, the proportion of resilient students is about 70 percent. In the United States, it is below 30 percent. These insights suggest that the United States’ educational system may be on a descending trajectory that could detrimentally affect the country’s economy and its social landscape (National Public Radio 2010).

Formal and Informal Education

Education is not solely concerned with the basic academic concepts that a student learns in the classroom. Societies also educate their children, outside of the school system, in matters of everyday practical living. These two types of learning are referred to as formal education and informal education.

Formal education

describes the learning of academic facts and concepts through a structured, programmatic curriculum. Arising from the tutelage of ancient Greek thinkers, centuries of scholars have examined topics through logical, systematic methods of learning. Education in earlier times was only available to the higher classes; they had the means for access to scholarly materials, plus the luxury of leisure time that could be used for learning. The Industrial Revolution, urbanization, the development of state-sponsored, publicly-funded institutions, and other social changes made education more accessible to the general population. Later, many families in the emerging middle class found new opportunities for schooling.

The modern U.S. educational system is the result of this progression. Today, basic education is considered a right and responsibility for all citizens. The United Nations outlines education as a basic human right in its Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Citation F), arguing that education must be free and universally-accessible. Expectations of this system focus on formal education, with curricula and testing designed to ensure that students learn the facts and concepts that society believes are basic knowledge.

Informal education

Describes learning about cultural values, norms, and expected behaviors through societal participation. This type of learning occurs in family homes, community spaces, and through the education system. Our earliest learning experiences generally happen via parents, relatives, and others in our community. Through informal education, we learn how to dress for different occasions, how to perform regular life routines like shopping for and preparing food, and how to keep our bodies clean.

Cultural transmission

Refers to the way people come to learn the values, beliefs, and social norms of their culture. Both informal and formal education include cultural transmission. For example, a student will learn about cultural aspects of modern history in a U.S. History classroom. In that same classroom, the student might learn the cultural norm for asking a classmate out on a date through passing notes and whispered conversations, as well as learning how to respectfully voice opinions and meet deadlines for assignments.

A Look at 4 Top School Systems

Every year, the OECD ranks education systems around the world from best to worst.

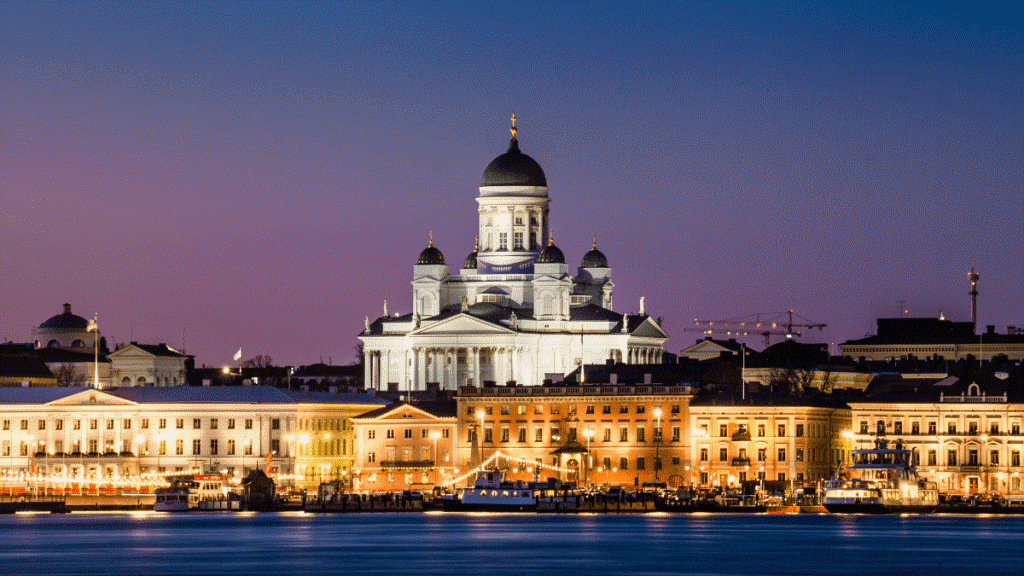

1. Finland’s Education System

Finland has long held first and second place, as one of the best education systems around the world. Although in recent years, it has lost ground to other countries, it still is a high performer, particularly with the Western style of education. In Finland, schooling does not begin for children until age 7. Homework and standardized testing are delayed until high school. In fact, there are no mandated standardized tests in Finland, apart from one exam at the end of students’ senior year in high school.

“Whatever it takes” describes the attitude of most Finnish educators, who are selected from the top 10 percent of the nation’s graduates to earn a required master’s degree in education. The transformation of Finland’s education system began about 40 years ago as a part of the country’s economic recovery plan. What is most striking about Finland’s education system is that the people running it, from the national to the local level, are educators. Equality is of the utmost importance, and students receive an equal education regardless of their backgrounds. Their children-first approach seems to be working well for this extraordinary education system.

2. Canada’s Education System

Canada is a newcomer to the top ten best education systems around the world. They don’t truly have a national education system, since education is divided by their autonomous provinces. The Canadian education system focuses on literacy, math, and high school graduation. Administrators, teachers, and their unions have created a curriculum that is successful across the country. Canada’s education system focuses on providing continued teacher training, transparent results, and a culture of sharing best practices. Students have many opportunities to prepare and practice for their future careers. Teacher morale is also high due to trust in teachers as professionals.

3. The Education System of Singapore

Singapore has risen to second place in the PISA rankings. This city-state has a technology-based education system, similar to Japan and Hong Kong. In 2004, Singapore’s government built a pedagogical framework called Teach less, Learn more. which encouraged teachers to focus on the quality of learning and asked them to incorporate technology into classrooms. The purpose was to shift focus away from the high-stakes testing environment that Singaporean classrooms traditionally valued.

Educational technology sets Singapore apart from many other countries. In classrooms, digital devices are viewed as a means to bring students together in collaboration, rather than using devices in isolation from other students.

4. South Korea’s Education System

In the past fifty years, South Korea has transformed its education system into one of the best in the world. South Korean students have six years of primary school, three years of middle school, and three years of high school. Coeducation schools are still rare in South Korea, with most students attending single-sex schools. Primary subjects include moral education, Korean language, social studies, mathematics, science, physical education, music, fine arts, and practical arts.

South Korea is known for having a rigorous, high-stress educational system, where families invest enormous time and money into providing the best education for their children. Public schools are free, but private schools and tutoring are available. Being a teacher in South Korea is a coveted position because of the high pay and high level of respect that teachers have. One remarkable achievement of their educational system? South Korea has accomplished a 100 percent literacy rate.

Educational systems around the world have many differences, though the same factors—including resources and money—affect every educational system. Educational distribution is a major issue in many nations, where the amount of money spent per student varies greatly by state. Education happens through both formal and informal systems; both foster cultural transmission. Universal access to education is a worldwide concern.

Leave a comment