The Taj Mahal, the most prominent monument of India, stands as a timeless symbol of love. The Taj was built by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan as a memorial for his deceased wife, Mumtaz Mahal. It is one of the seven wonders of the world and is the pride of not just Agra but also of India. He said it made “the sun and the moon shed tears from their eyes”. Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore described it as a “teardrop on the cheek of eternity.”

Its name is believed to have been drawn from Persian: ‘taj’ meaning crown and ‘mahal’ meaning palace, thus making this the ‘palace of the crown’. Interestingly, the queen in whose memory it was built, originally named Arjumand Begum, held the name ‘Mumtaz Mahal’, meaning ‘the crown of the palace’. The Taj Mahal is known as a monument of love and a grieving emperor’s ode to his beloved deceased queen. Another legend considers the Taj as an embodiment of Shah Jahan’s vision of kingship. The story goes that he sought to build something akin to heaven on earth, a spectacular and unbelievably beautiful monument that reinforced the power, as well as the perceived divinity of the monarch, as next only to the Almighty.

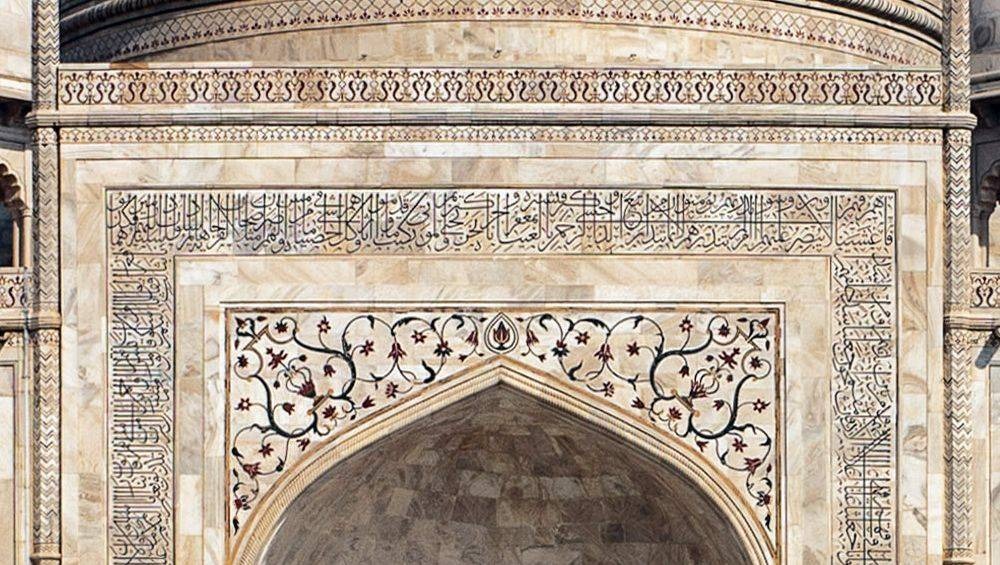

It is also commonly accepted that Ustad Ahmad Lahori oversaw the project, Ustad Isa created the site design, and Emperor Shah Jahan recruited artists from Italy and Persia to work on this marble monument. Amanat Ali Khan Shirazi is credited with the calligraphic art, while Ran Mahal, a Kashmiri designer, created the gardens.

This construction is interesting because, other from the side facing the River Yamuna, it appears identical from every angle. It is stated that side was carefully decorated to act as the emperor’s main entrance. While the current tourist entrance to the Taj Mahal serviced soldiers and commoners, Shah Jahan would approach the structure from the river on a barge.

Construction History

The complex’s designs have been credited to a number of historical architects, although Ustad Aḥmad Lahawrī, an Indian with Persian ancestry, was most likely the principal designer. The main gateway, garden, mosque, jawāb (literally, “answer”; a building mirroring the mosque), and mausoleum (including its four minarets) are the five principal elements of the complex. They were conceived and designed as a unified entity in accordance with the principles of Mughal building practice, which forbade any later additions or alterations. Construction started in 1632. The mausoleum itself was constructed by around 1638–1639 thanks to the labor of almost 20,000 artisans hired from India, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and Europe; the auxiliary buildings were completed by 1643, and decorative work went on until at least 1647. The 42-acre facility took 22 years to build in total.

Arrangement & Design

The actual mausoleum, which is 23 feet (7 meters) high and rests atop a broad plinth, is made of white marble that changes color depending on the amount of sunshine or moonlight. It features four virtually identical facades, each with a chamfered corner that incorporates a smaller arched area and a broad central arch that rises to 108 feet (33 meters) at its peak. Four smaller domes surround the imposing central dome, which rises to a height of 240 feet (73 meters) at the tip of its finial. A flute note reverberates five times due to the acoustics within the main dome.

The mausoleum’s interior is arranged around an octagonal marble chamber that is embellished with semiprecious stones (pietra dura) and low-relief decorations. The cenotaphs of Shah Jahān and Mumtaz Mahal are located there. There is a beautifully carved marble screen made of filigree surrounding the bogus tombs. The actual sarcophagi are buried beneath the graves, at garden level. Elegant minarets are situated at each of the four corners of the square plinth, beautifully separating it from the center edifice.

Two symmetrically identical buildings flank the mausoleum in the northwest and northeastern sides of the garden, respectively. The mosque faces east, while its jawāb faces west, providing an artistic balance. The red Sikri sandstone domes and architraves, along with the marble-necked domes, create a striking contrast in both color and texture when compared to the white marble mausoleum.

With walking walkways, fountains, and decorative trees, the garden is laid out in the traditional Mughal style, with a square divided into quadrants by lengthy watercourses. Enclosed by the complex’s walls and structures, it offers a spectacular approach to the mausoleum, which is reflected in the central waters of the garden.

A large red sandstone entrance with a two-story-tall recessed central arch graces the complex’s southern end. Black Qurʍānic text and floral motifs are inlaid into the white marble paneling that encircles the arch. Two pairs of lesser arches flank the main arch. Matching rows of white chattris, eleven on each façade, crown the northern and southern facades of the gateway. They are accompanied by slender, ornamental minarets that reach to a height of around 98 feet (30 meters). Octagonal towers with larger chattris on top are located at each of the structure’s four corners.

The structure repeatedly uses Arabic calligraphy and pietra dura, two prominent decorative elements. Pietra dura, which means “hard stone” in Italian, is a Mughal art form that combines highly structured and intertwined geometric and floral designs with the inlay of semiprecious stones in a variety of colors, including as lapis lazuli, jade, crystal, turquoise, and amethyst. The vibrant expanse of the white Makrana marble is subdued by the colors.

Calligraphy, a fundamental aspect of Islamic artistic tradition, was used to inscribe Qurʍān verses throughout various sections of the Taj Mahal, overseen by Amānat Khan al-Shīrāzī. The devout are invited to enter paradise by Daybreak, one of the inscriptions in the sandstone entrance. The lofty arched doorways of the mausoleum proper are likewise surrounded by calligraphy. In order to maintain consistency when viewed from the terrace, the lettering enlarges in proportion to its height and distance from the observer.

Current Issues

The foundation of the Taj Mahal is made of rocks and is located below the water table. The high volume of visitors to the Taj Mahal’s grounds has resulted in a variety of problems, such as pollution, a loss of open space, the degradation of the historic site, cultural effects, and aggravation from tourists’ behavior. Due to the excessive humidity brought on by overcrowding, water droplets began to seep through the chamber walls, causing damage to the inlay work. Marble was found to be extremely corrosive when it was first wrongly thought to be a safe material. Unusual scribbling practices by visitors have also damaged the precious stone. The government had to assign conservators to oversee the monument and install CCTV cameras in order to monitor these problems.

Leave a comment