What is the Halo Effect?

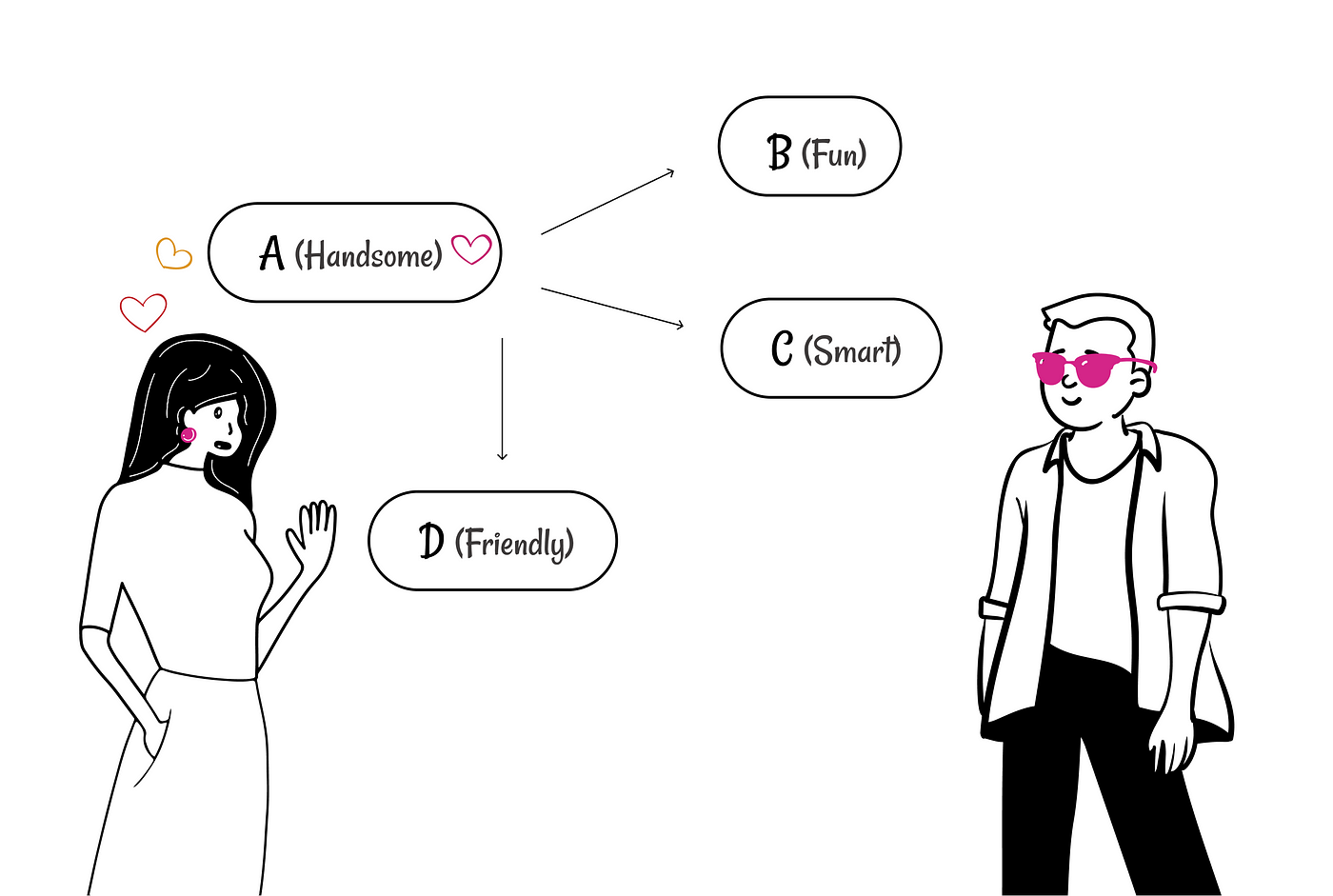

The halo effect is a type of cognitive bias in which the overall impression of a person influences how others feel and think about a person’s specific traits.

It claims that positive impressions of people, brands, and products in one area positively influence our feelings in another area. For example, “He is nice!” affects the perception of other particular characteristics (“He is also smart!”). Perceptions of a single trait can carry over to other aspects, too.

The halo effect is also sometimes referred to as the physical attractiveness stereotype and the “what is beautiful is also good” principle. However, the halo effect can encompass other traits as well. For example, people tend to see others who are sociable or kind as likable and intelligent, too.

The halo effect allows perceptions of one quality to spill over into biased judgments of other qualities. The expression draws on the image of a halo, which casts a positive light on what it surrounds; thus, the “halo” created by the perception of one characteristic can cover others in the same way.

The Term ‘Halo’

The halo effect is named in connection with the religious symbol. Crowing the heads of saints, a glowing halo bathes their faces in light. Fittingly, the halo effect causes us to think highly of people, often due to their outward appearance, or based on one quality that we value.

Examples of Halo Effect

A common halo effect example is attractiveness, and the tendency to assign positive qualities to an attractive person. For example, you might see a physically beautiful person and assume they are generous, smart, or trustworthy. This bias is so common that the halo effect is sometimes generalized to refer to the specific assumption that “what is beautiful is good”.

One study showed that people make these assumptions about youthfulness, too. People are more likely to have more favorable perceptions of people with a younger, baby-like appearance than those who appear older.

Where this bias occurs

The halo effect often occurs when we consider appearances. A classic example is when one assumes that a physically attractive individual is likely to also be kind, intelligent, and sociable. We are inclined to attribute positive characteristics to this attractive person even if we have never interacted with them.

The halo effect is an error in our judgment and reflects individual preferences, prejudices, and social perception. While biases can create an impact on an entire group, the halo effect can also be individualized. For example, if you specifically value one brand of hair care products, you may be likely to evaluate their new line as amazing, even if it has terrible reviews.

Why it happens

The halo effect occurs because human social perception is a constructive process. When we form impressions of others, we do not rely solely on objective information; instead, we actively construct an image that fits in with what we already know. Indeed, the fact that we sometimes judge another person’s personality based on their physical attractiveness seems incorrect, but research continues to demonstrate the effect.

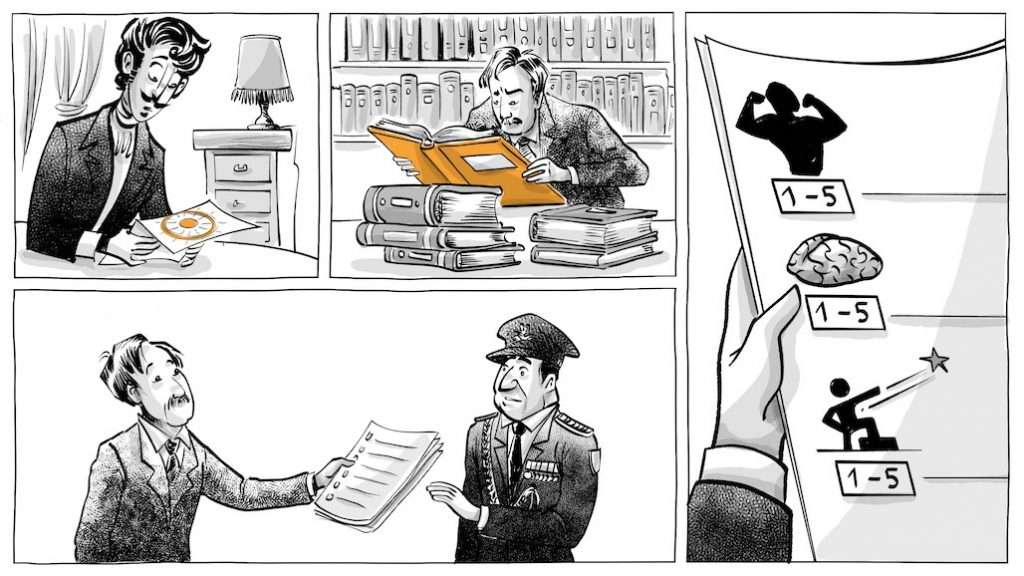

History

Research on the phenomenon of the halo effect was pioneered by American psychologist Edward L. Thorndike, who in 1920 reported the existence of the effect in servicemen following experiments in which commanding officers were asked to rate their subordinates on intelligence, physique, leadership, and character, without having spoken to the subordinates. Thorndike noted a correlation between unrelated positive and negative traits. The service members who were found to be taller and more attractive were also rated as more intelligent and as better soldiers. Thorndike determined from this experiment that people generalize from one outstanding trait to form a favourable view of a person’s whole personality.

In 1946, Polish-born psychologist Solomon Asch found that the way in which individuals form impressions of one another involved a primacy effect, derived from early or initial information. First impressions were established as more important than subsequent impressions in forming an overall impression of someone. Participants in the experiment were read two lists of adjectives that described a person. The adjectives on the lists were the same but the order was reversed; the first list had adjectives that went from positive to negative, while the second list presented the adjectives from negative to positive. How the participant rated the person depended on the order in which the adjectives were read. Adjectives presented first had more influence on the rating than adjectives presented later. When positive traits were presented first, the participants rated the person more favourably; when the order was changed to introduce the negative traits first, the same person was rated less favourably.

How the Halo Effect Affects Daily Life

Presumptions can be helpful. They allow you to notice your surroundings and quickly judge whether you’re safe. They also help you socially and allow you to fill in unspoken information about others that guide your response. For example, you might notice someone crying, assume they’re sad, and seek to offer comfort. However, biases like the halo effect can influence everything in your awareness, right down to the food you buy, and distort the truth unhelpfully.

Marketing plays on your perceptions. Images and information on labels can influence your view of a product, making something seem healthy even if is not. It’s hard to escape biases, though, and it takes conscious effort and self-awareness to get beyond them. It’s possible that you might view other people or things through the halo effect, and other people most likely do the same to you. You experience such biases in almost every part of your daily life.

Halo Effect and Work

The halo effect is often at play in your workplace. You might learn your coworker went to a prestigious university and assume they’re more qualified, even if they aren’t. If your colleague dresses sharply, you might assume they’re a hard worker, but that might not be true. Unfortunately, the halo effect can also interfere with your earnings. Thorndike’s original study with the officers and soldiers is a good example of workplace bias, but modern research also shows these effects. In one study, attractive female restaurant servers earned about $1200 more a year in tips than their so-called unattractive coworkers. The study found that female customers tipped beautiful female servers more than they tipped male servers or unattractive female servers.

Halo Effect and Health

Research on packaging information shows that you’re likely to think a food is healthier than it is based on the nutrition claims. When a package labels a granola bar as a “ protein bar”, for example, you’re more likely to assume the bar is healthy, even if the label clearly shows it has lots of sugar and calories. Another example is the term “organic.” In one study, researchers used the same foods but gave some people an organic label and others a regular label. Those with the organic label had an overall higher perception of the food. They liked it more, were willing to pay more for it, and assumed it was healthier and had lower calories than it did. They also had more positive emotions toward the food.

Halo Effect and Medicine

You often use the halo effect to judge the quality of your medical treatment, too. One study showed that patients who had a good “hotel” experience at a hospital gave the hospital a higher overall rating. The rating had nothing to do with medical treatment, patient safety, healthcare quality, or even a lower risk of dying. If the room was quiet and the nurses talked to them, patients had a higher impression of the treatment they had received. Unfortunately, the halo effect can also influence how others view your health. If you are nicely groomed or attractive, someone might assume you’re healthy or you have good mental health. In reality, these things can be unrelated, and you can’t always tell when someone is unwell.

Halo effect and AI

If done properly, artificial intelligence can actually help to mitigate the halo effect. To illustrate, certain companies implement AI software to scan job applications and weed out potential candidates from those who may not be qualified. Filtering out certain, bias triggering, information and evaluating based on defined job criteria can help to eliminate human error and the tendency toward the halo effect. For example, if a particular manager completed their schooling at X university, they may think that others who attended this university share his values and may be biased to believe that they will be the best fit for the role.

It is important to remember that AI software is not completely bias free. Everything from the data it uses to make predictions to the programmers who create the systems can cause biased output. However, this too can be fixed, it is a lot easier to point out bias when we are not the ones perpetrating it. If we catch a system following that same human pattern we can address and correct it.

The Reverse Halo (or Horn) Effect

As the name implies, the reverse halo effect occurs when a person judges another negatively based on only one known characteristic. That single trait colors all of the others for someone experiencing the reverse halo effect. For example, a person might assume that someone they view as unattractive is also unkind.

Leave a comment